After sorting, roasting, and winnowing, it’s time to begin refining. This is the step in the chocolate making process when the solid nibs begin to take the liquid form of melted chocolate.

The best analogy here is that of almond or peanut butter: Take a few nuts, send them through a simple mill and voilà! you have a mostly liquid paste of nuts. The same goes for chocolate…

Disclaimer: To the purist, “refining” might carry a bit of negative connotation. But for us, refining our chocolate doesn’t involve anything… unnatural. We’re just making the nibs and sugar crystals smaller using old fashion techniques.

Important basic concept #1: There is no water in the nibs, sugar, or resulting chocolate.

Important basic concept #2: Because there is no water present, sugar does not just simply dissolve into the chocolate paste.

Important basic concept #3: Cacao beans are composed of about 50% fat (+/-), which is commonly referred to as cocoa butter. Similar to nuts, the fat is released during the grinding process. When this fat is released, it acts to coat and suspend the solid cacao and sugar particles. With some origins, the cocoa butter content is naturally so high that no additional cocoa butter is needed, as is the case with our Belize and Peru chocolates.

Our first step in the refining process is to do an initial grind of the nibs to create a rough, bitter paste. We then add this paste to the melangeur (French for mixer). The melangeur accomplishes two goals: 1. it mixes the sugar with the cacao paste; 2. it begins breaking the cacao and sugar particles into a finer state.

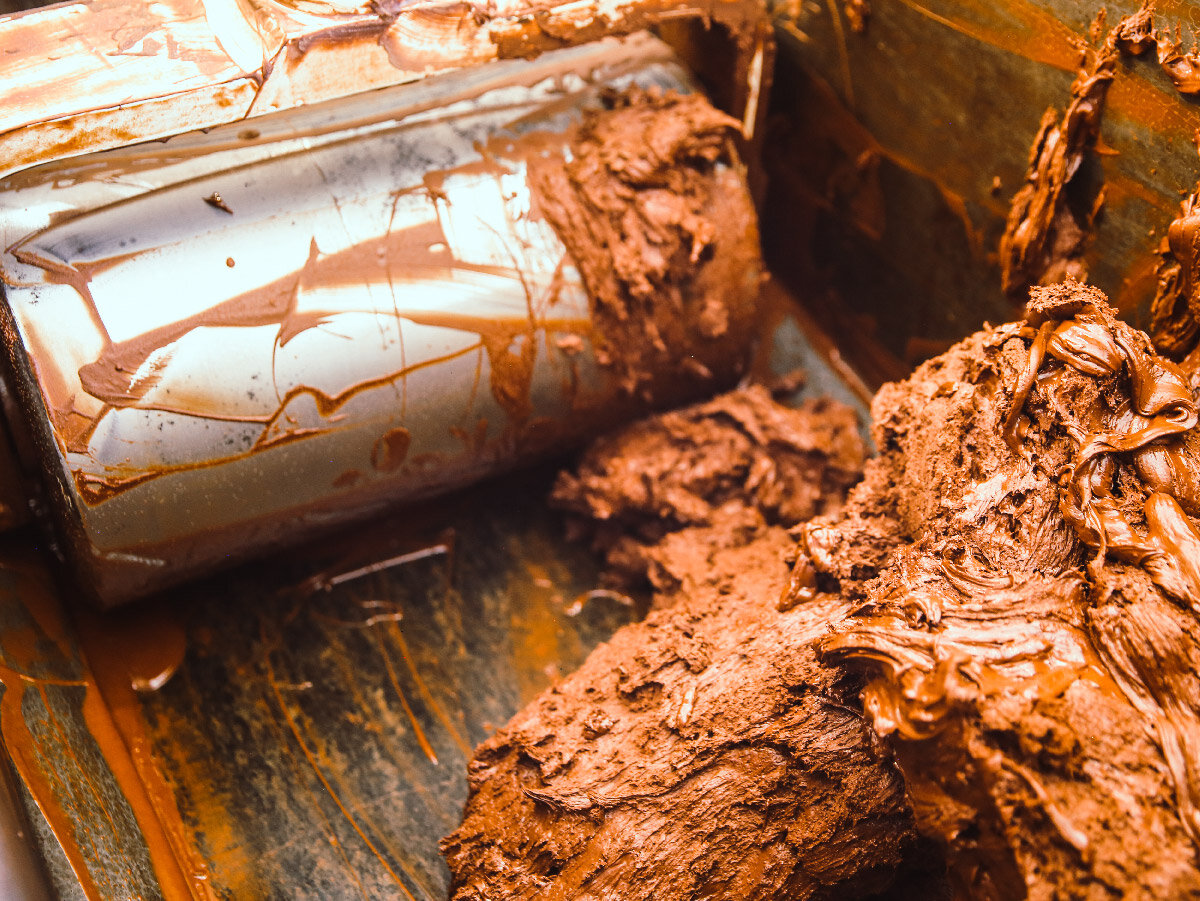

After the melangeur it’s time to further break down the chocolate particles in our three roll mill. The roll mill is a series of long, round rollers pressed tightly against one another.

The rollers spin in different directions, the center in opposition to the outside rollers. Each consecutive roller spins faster than the last. This accomplishes two things—1. the faster spinning roller “grabs” the chocolate off of the previous roller 2. It creates a tremendous amount of shear force. After the chocolate has passed through several roller contact points it begins to resemble the smooth texture of what we know as chocolate. The particles are now broken down to around 10 - 15 microns in diameter, making our chocolate extremely smooth with almost no detectable particles.

On a side note, the shear and friction created by the rollers creates a lot of heat. The temperature of the rollers are maintained by a constant flow of cool water inside of the rollers. Without the cooling effect of the water, the heat would cause the rollers to expand and exponentially produce more friction until they’d begin to self destruct in quite a dramatic fashion. As you can imagine, we try to avoid this. We’ll leave you to imagine what would happen if our roll mill ever got out of control.

At this point our chocolate is ready for the longitudinal conche.

The purpose of the conche is to develop the flavor and improve the texture of the chocolate. This is accomplished by keeping the chocolate warm, grinding it with the conche rollers, and splashing it against the walls of the roller tanks for three days continuously.

One of the main reasons we use a conche is to improve the acidity of the chocolate. There are several different types of acids that are present in the cacao bean, some help improve flavor while others hurt flavor. Roasting and conching are balancing acts between removing the bad acids and taming the good. All of our chocolate gets a standard 3 days of conching. If a certain type of cocoa bean is particularly acidic we can can adjust for that in the roast and/or increase the conching temperature. Through constant agitation of the chocolate the conche produces an environment in which the volatile acids evaporate from the chocolate, leaving our chocolate tasting pristine, delicious, and balanced.

In case you weren’t keeping track, from sorting the beans to emptying the conche it takes 7 days to make one big 1,200lb batch of chocolate and even then the process is not over—we still need to temper, mold and wrap. This seemingly long process is the culmination of all the principles we’ve learned along the way—through books, mentors and experience. Through this method we’re making a better chocolate than can be produced by modern methods and technologically “advanced” chocolate making machines.